The year is 199X

A young boy has arrived in a quiet Midwestern town. There is a package waiting for him, from the best friend he had to leave behind in the sunny Southwest. In it, a homemade card featuring the Talah Rama, guru of the Monkey Cave.

When good friend leaves, Wise Talah Rama say...

This sucks.

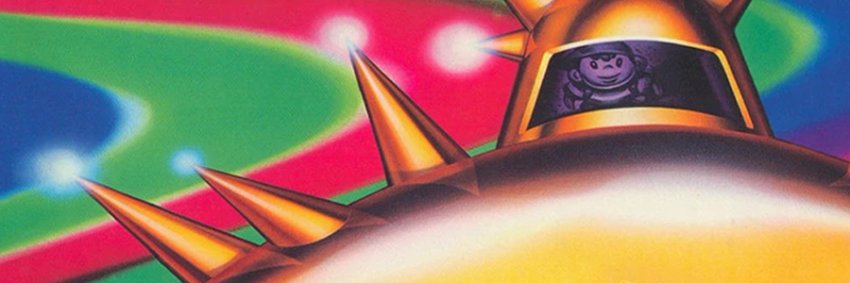

It was a fitting companion to the other items in the package: a copy of Earthbound for the Super Nintendo, along with its 130-page manual that doubled as a strategy guide that doubled as a travel guide to the world of Eagleland. My friend knew that the game had made a huge impression on me when he had lent it to me the year before, and he guessed that I could use something to take the sting out of moving.

He wasn't wrong. I had moved before, with my mother being an officer in the Air Force, but this time felt different. I missed my friends each time, but this was the first time I'd had to leave an entire group of friends who truly felt like family. We stayed at each other's houses seemingly every weekend. We called each other's parents Mom and Dad on occasion. We nicknamed each other, spent every lunch and recess together, had an ever-changing set of in-jokes.

And we played games together. Practically every free minute. Online multiplayer hadn't yet come to consoles, so the best way to play with your friends was to sit on the couch or floor together, controllers wired across the living room, blasting each other in Goldeneye or working out the impossible free-fall shortcuts to be had in Mario Kart 64's Rainbow Road. Handheld gaming was reaching a fever pitch with the arrival of digital pets. Tamagotchi, Digimon, and Pokémon practically required us to switch to cargo pants, and if we weren't surreptitiously checking their health and training during class, we were fighting them or trading them in the schoolyard. Meanwhile at home, PC gaming was in its prime, (not to mention dial-up internet-enabled), allowing us to scour the dungeons of Diablo together, frag each other in Quake 2, or show off our design and storytelling skills in the oddball new MMO genre with games like Graal. Even if we weren't playing games, we were talking about them through IRC with other like-minded kids in chat rooms like Kakariko Village Square, dedicated to Legend of Zelda enthusiasts.

All of these games stick with me to this day, but Earthbound was something special. It was single-player, and made for the previous generation of consoles, which meant I had the means to enjoy it at home by myself as though I was enjoying a good book. I had played other games this way, usually rented from the video store or lent to me by friends: Chrono Trigger, Harvest Moon, E.V.O.: Search for Eden. But while these games made for a wonderful long weekend, Earthbound was the first one to achieve the goal of art, to elicit emotions. Laughter, melancholy, fear, hope.

The game and its Japanese counterparts, the Mother series, are widely known for the zealous fanbase they've attained. Few if any other video games have inspired the same amount of artwork, music, writing, programming, discussion, and, crucially, friendships. I certainly wasn't alone in writing my countless drafts of an Earthbound movie script, my attempts to devise an Earthbound tabletop RPG, my colorful clay sculptures of the characters made in middle school art class. After worldwide fans at Starmen.net learned that the game's sequel, Mother 3, was relegated by Nintendo to a Japan-only release on the Game Boy Advance, they famously created a 400+ page, professionally bound book to petition for Mother 3's English localization. Containing over 30,000 hand-written fan signatures, along with hundreds of pieces of art, comics, and music, four copies of the book were sent to Nintendo of Japan, Nintendo of America, the magazine Electronic Gaming Monthly, and the creator of the series, Shigesato Itoi. When this unprecedented act failed to convince Nintendo, one fan took it upon himself to localize the entire game anyway and release it to other fans desperate to connect with Earthbound's descendant.

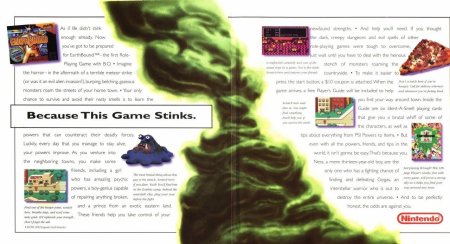

Unlike other video games of its day, with their sleek starships and Arthurian warlocks, Earthbound was unique in being about us. Four kids, Ness, Paula, Jeff, and Poo, against a world gone mad. There were no health potions to be found, only hamburgers. The "Non-Stick Frypan" was a mighty weapon to be feared. Enemies were often comically banal, from the "Spiteful Crow" to my personal favorite, the "Unassuming Local Guy." There were fart jokes. It's North American ad campaign famously, and perhaps inadvisedly, declared "This game stinks."

But beyond it's quirky humor and outlandish plot, Shigesato Itoi had managed to create something fundamentally relatable. A malicious alien, defeated once in the first Mother installment, has returned to feed on the world's evil nature, slowly turning people and animals against each other. Authority figures dawdle during the crisis. The cops actively impede your progress. Money-obsessed old men seem to be pulling the strings without regard for others. Presciently, your nemesis Pokey is an overweight, pathological liar with a terrible blond haircut and a thirst for power. Adults, it seems, have given up.

Like many works of art, I've enjoyed Earthbound in new ways each time I've returned to it. As a boy living in Tucson, I was of course delighted when Ness reached the game's second town, Twoson, (following Onett and before Threed and Fourside, obviously). But I was most struck by the Act Two "coffee break," in which the game's author suddenly talks directly and sincerely to the player:

You've traveled very far from home...

Do you remember how your long and winding journey began with someone pounding at your door? It was Pokey, the worst person in your neighborhood, who knocked on the door that fateful night.

On your way, you have walked, thought and fought. Yet through all this, you have never lost your courage. You have grown steadily stronger, though you have experienced the pain of battle many times.

You are no longer alone in your adventure, Paula who is steadfast, kind and even pretty, is always at your side. Jeff is with you as well. Though he is timid, he came from a distant land to help you. Ness, as you certainly know by now, you are not a regular young man... You have an awesome destiny to fulfill.

The journey from this point will be long, and it will be more difficult than anything you have undergone to this point. Yet, I know you will be all right. When good battles evil, which side do you believe wins? Do you have faith that good is triumphant?

One thing you must never lose is courage. If you believe in the goal you are striving for, you will be courageous. There are many difficult times ahead, but you must keep your sense of humor, work through the tough situations and enjoy yourself.When you have finished this cup of coffee, your adventure will begin again. Next, you must pass through a vast desert and proceed to the big city of Fourside.

Ness... Paula... Jeff...

I wish you luck...

As a young man I would come to appreciate the game's exploration of loneliness and mental demons like depression. Like Ness, I had also journeyed far from home to the big city of Los Angeles, my parents supporting me from afar like his. In the game, as in life, Ness will occasionally fall victim to "homesickness." Thus afflicted, he randomly gets distracted in battle with flashes of memories from home. My own therapist's advice wasn't far from the in-game doctor's: "What a sad look in your eyes... That's nothing you need to be ashamed of. Anybody who is on a long trip will miss home. In this case, the best thing to do is to call home and hear your mom's voice." Itoi has mentioned in interviews that the series' name, Mother, was inspired by the John Lennon song of the same name, a heart-wrenching ode to missing parents. At one point in the game, Ness witnesses a vision of his own mother as a young woman. At another, his father holding him as a child.

As an adult I found myself drawn to Zen Buddhism, and Earthbound was likely my first introduction to some of its tenets. The last character to join your party, Poo, hails from the distant Dalaam. In a test of his training in the philosophy of "Mu," he is required to meditate while his mind plays tricks on him, and a bizarre spirit seems to destroy his limbs one by one, then his ears, then his eyes, and finally Poo's own mind. Only by recognizing the illusions presented to us by our body do we discover our identity, synonymous with the world we see. Or, as the wise guru Talah Rama puts it in game,

The truth of space and time moves through the universe like a wave...

Later on, Ness is thrust into the recesses of his own mind: once through a drink possibly laced with psychedelics, and another time through a lucid dream. Language becomes confused, colors go wrong, and people from his past appear at random to give advice. To succeed, he's forced to enter his own nightmares, and face his evil side head-on, alone. As the saying goes, "the only way out is through."

I found myself recently crying in front of my therapist when I told her the story of my best friend's package. I lost the strategy guide somewhere along the way, but the game still sits on my shelf, next to the toy of Ness, and my handmade sculpture of his oddball helper, Mr. Saturn. Like Ness, I've traveled to many cities across the world, making new friends, battling my demons, and learning new powers. The adults still don't seem to have grasped the nature of the evil enveloping the world, and my nemesis has a frightening amount of power. But also like Ness, I am no longer alone in my adventure. Catherine, who is steadfast, kind and definitely beautiful, is always at my side. And, like Paula in Earthbound's final moments, I suspect that it may be her empathy that finally releases the evil from this world.